Think Again | The Art of Changing Idea

Personal summary of the book "Think Again", by Adam Grant

Published on May 22, 2024 by Erik Pillon

article post review

5 min READ

It doesn’t happen often that I get as positively surprised as while reading the book by Adam Grant “Think Again”. After reading and taking several notes for my zettelkasten system, I can genuinely say that I’m sitting in front of a masterpiece. I was honestly not familiar with any of the work but it was an absolute pleasure to dig into all the amazing material available online. Albeit being an extremely proficient writer, Adam Grant is also a (multiple times) TEDx speaker and a true polymath: while having a background in social psychology the author can connect a lot of different branches of human knowledge and provide a unified holistic personal view of the world.

Synopsis

The manuscript is a long essay about making ideas and changing them: it is often the case that while a few elements allow us to make an opinion, the same number of elements is not enough to let us change it. The entire book is devoted to explaining why and the consequences that we face if we indeed do change our mind or not. Intro

The book is divided into three parts, that abstract the three levels where rethinking acts: personal level, interpersonal level, and sociological level. The book builds from the fundamental principle that being human, not only do we fall trapped constantly in several biases, but most importantly we even experience the “I’m not biased” bias. It is therefore important to not only be aware of the fact that what we consider universally true might be wrong but also that what used to be true in the past might not be true in the future. Knowledge is a never-ending building process and as such, needs to be constantly built, challenged, destroyed, and rebuilt.

“Arrogance is ignorance plus conviction”

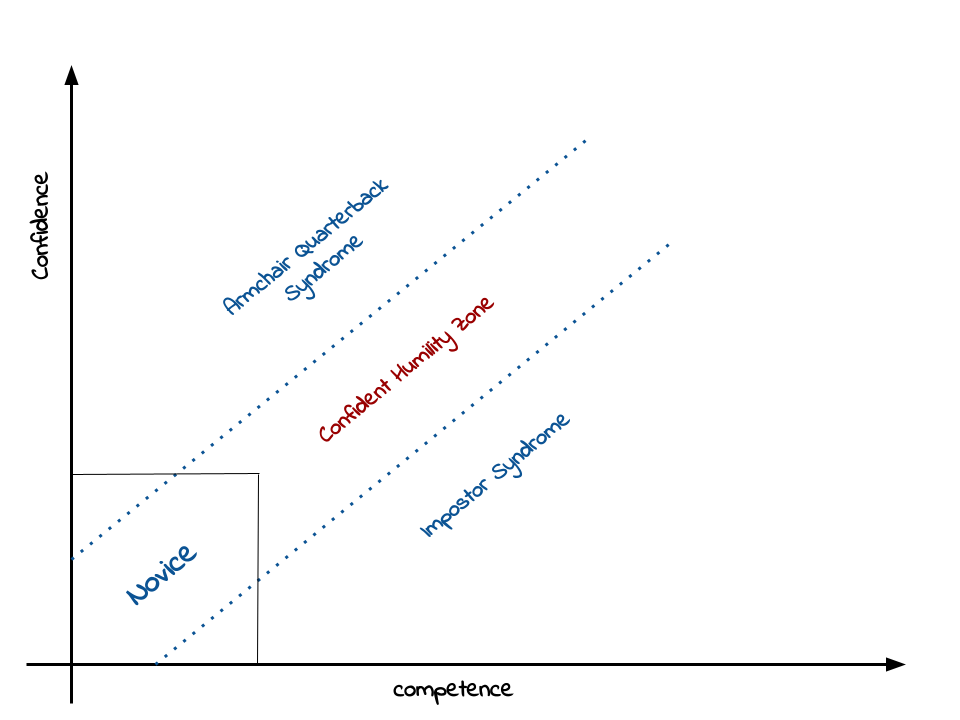

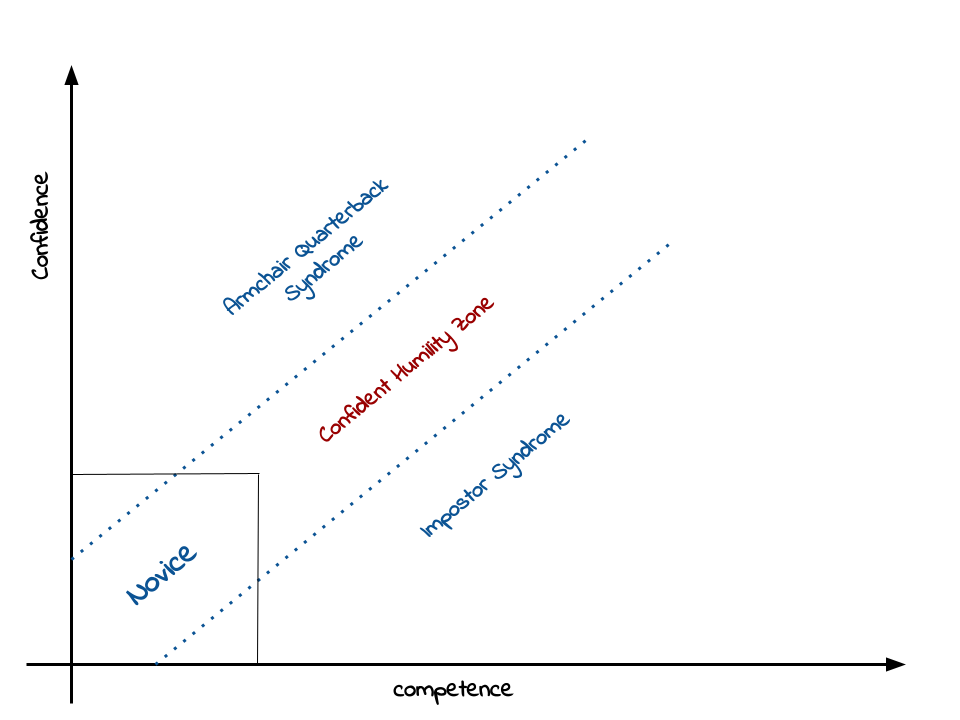

Chapter 2 demystifies the effects of self-confident attitudes towards problems and unknowns. The two extremes of the behaviors that we can adopt while facing something new and difficult are from one side the “armchair quarterback syndrome” (i.e., being too arrogant and self-confident), while on the other we have the impostor syndrome, leading to chronic immobilism and insecure behavior. Finding the right balance in the middle, what the author calls the “confident humility zone”, is our goal. We receive from society constant explicit encouragement to always adopt a more self-confident approach to problems and tasks in life (after all, all the successful people that we see every day appear to be extremely self-confident) but the author argues that there’s plenty of evidence in the academic literature that confidence is often the results of achieving results, not the cause of it.

Arrogance leaves us blind to our weaknesses. Humility is a reflective lens: it helps us see them. Confident humility is a corrective lens, it enables us to overcome those weaknesses.

Chapter 3 helps us understand how we can take a proactive approach to rethinking and challenging our positions. Discovering ourselves wrong should not be a painful moment, but instead a joyful and positive one: we just learned something new after all! Overcoming the sense of ignorance and conviction employing the pleasure that we get from our recent discovery should be the driving factor in challenging the small “dictator” that we have in our head that keeps us anchored to our old position (see also “Think fast and slow” by Daniel Kahneman in these regards). Chapter 4 follows immediately on this topic and shows us how to overcome a conflicting position not only with ourselves but also with other people, thus opening the topic of conflict resolution and collective thinking. As Hegel said, the ideal synthetic process always comes from the solved conflict between an idea and its antithesis.

Chapter 5 is about debating and convincing your audience or your interlocutor. Convincing someone is not a matter of being better documented (falling trap of the argument dilution) or having a longer list of scientific pieces of evidence (and thus alienating your audience), but of having the best argument and the best attitude. When documenting yourself and trying to make an opinion, don’t forget to also train yourself in conveying that idea and that opinion. The second section ends with a discussion about prejudices and stereotypes and the role of mediators in debates. Motivational interviewing is also discussed and is shown how an active listener can help decision makers to get to a “yes”.

Section 3 is a beautiful investigation into accepting inconvenient truths, accepting the cyclic nature of the (re-)learning process, and overcoming the “we always did this way” attitude. There’s no such dangerous thing in associations and companies as these 5 words. Being open to improvements, adjustments and changes is the key to success in the long term. The author claims that a fundamental step in this direction must be taken by teachers and educators: already from the early school years, students should be not taught to learn concepts, but rather to rethink concepts and to appreciate the rediscovery of an old concept in a new way or under a new perspective.

Conclusion

All in all, this is a wonderful book that made me think a lot, both on how I make my own opinions and on how I change them (either individually or as part of a society). Unlike many others, this book puts at the center not the knowledge itself but the learning process, emphasizing the importance of rethinking and unlearning, while always keeping a flexible, humble, and open mindset.

I was not particularly familiar with Adam Grant, the author of this book, but after checking him out on the web I discovered tons of amazing material that investigates different and collateral topics of this manuscript.